Stories

• As a community that’s always making new things, we love to share experiments, new learnings, and interesting iterations of time-tested tools. Here’s a look inside: works-in-progress, projects of impact, and our reflections on all of it.

Story

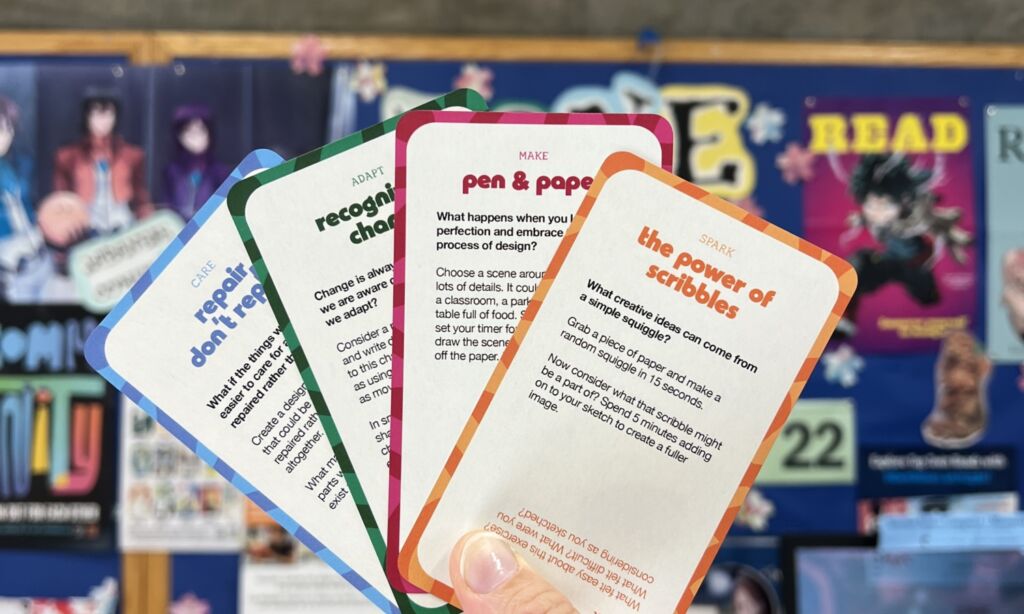

A Deck of Design Values • Sparking curiosity, empathy, and courage in those new to design mindsets

How we worked with Amplifier to create a first-of-its-kind card deck rooted in design values,…

K-12

Story

The Hidden Emotional Work of Strategy and Design

Social Impact

Story

Why Strategy and Human-Centered Design Belong Together

Social Impact

Story

Embedding Ethics in Design Education: Helping students apply ethical reasoning to real-world design…

Story

Ahmad Abubaker: A 2025 Personal Statement Night Highlight

Graduate

Story

Kavya Udupa: A 2025 Personal Statement Night Highlight

Graduate

Story

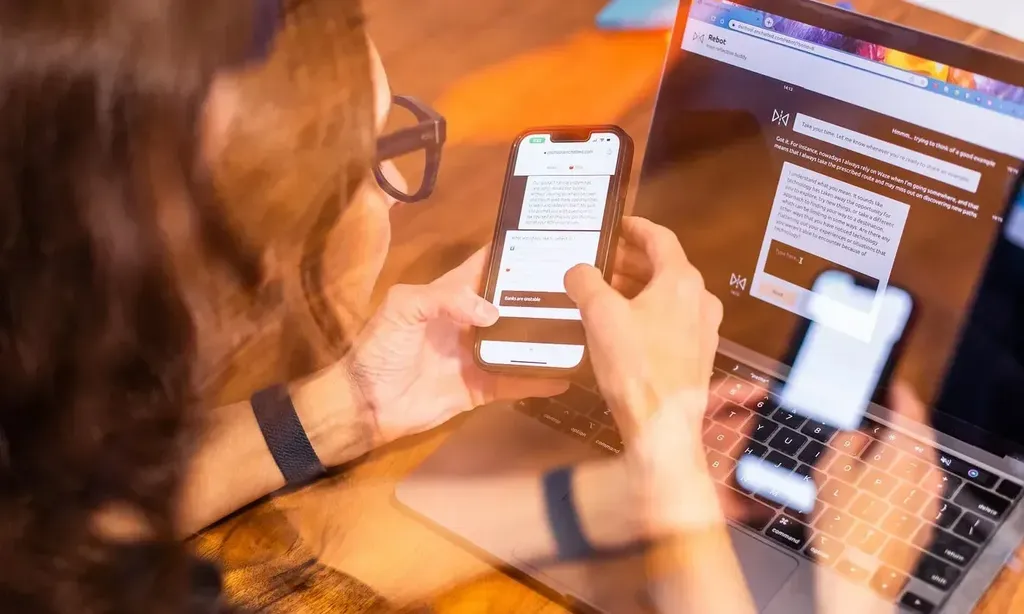

From Overwhelm to Impact: How Project Scoping Unlocks Better Social Change–and How Our AI Tool…

Emerging Tech

Story

Arianne Spalding: A 2025 Personal Statement Night Highlight

Graduate

Story

Mollie Redman: A 2025 Personal Statement Night Highlight

Graduate

Story

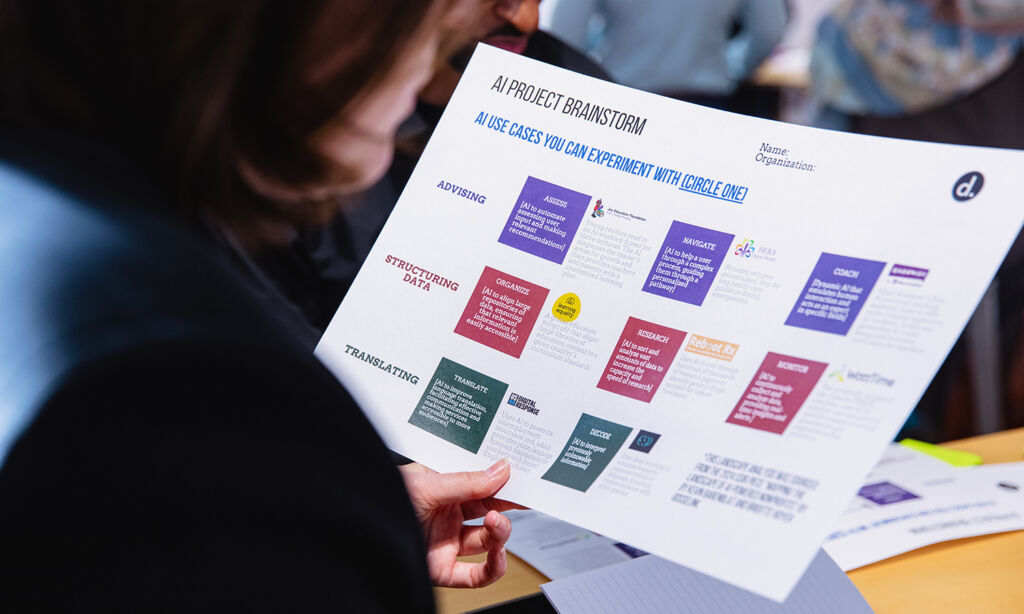

Designing Human-Centered AI for Social Impact: Using AI to Serve the Public Good, Part One

Emerging Tech

Story

How Our Creativity Is Evolving Alongside AI: Creativity in the Age of AI, Part Three

Emerging Tech

Story

Why AI Makes Design Skills More Valuable Than Ever: Creativity in the Age of AI, Part Two

Emerging Tech

Story

Let’s Not Make AI the “Easy Button”: Creativity in the Age of AI, Part One

Emerging Tech

Story

Harrison Lin: Design Master's Degree Spotlight

Graduate

Story

Kalina Yang: A 2025 Personal Statement Highlight

Graduate

Story

Koh Terai: A 2025 Personal Statement Highlight

Graduate

Story

Izma Shabbir: A 2025 Personal Statement Highlight

Graduate

Story

Natalia Chen: A 2025 Personal Statement Highlight

Graduate

Story

Mario Garcia Causapié: A 2025 Personal Statement Highlight

Graduate

Story

Brigid White: MS Design Student Spotlight

Share Out

Story

Transforming City Services Through Human-Centered Design

Impact

Story

A New Community of Designers

Share Out

Story

Reflecting with AI

Share Out

Story

Design for Democracy: Investigating Election Administration

Project

Story

Building Future Foundations

Share Out

Story

Future's Happening: Democracy Edition

Project

Story

Stanford’s Two New/Old Design Degrees

News

Story

(in)Visible Designers

Share Out

Story

Reimagining Higher Ed: The Stanford 2025 Project

Project

Story

Work Toward Equity: Sound Practice Podcast

Project

Story

How To Write: Rituals and Reminders from the Stanford d.school

Share Out

Story

Saad Riaz: Design Master's Degree Spotlight

Share Out

Story

Positive Deviance for Educators

Project

Story

d.school Yearbook 2023-24

Share Out

Story

Laura Schütz: Developing Sound-Guided Surgery Tools

Impact

Story

Let's Stop Talking about THE Design Process

Share Out

Story

Educator Guides: Activities from d.school Books

Share Out

Story

d.school Yearbook 2022-23

Share Out

Story

Designing (Ourselves) for Racial Justice

Project

Story

Practicing Radical Collaboration: Q&A with Domain Co-Lead Emily Callaghan

Share Out

Story

Designing a Sex Ed Program for Students with Developmental Disabilities: A Case Study

Impact

Story

Burt Herman: Hacks/Hackers

Impact

Story

d.school Yearbook 2021-22

Share Out

Story

Ben Knelman: Engineering Financial Literacy

Impact

Story

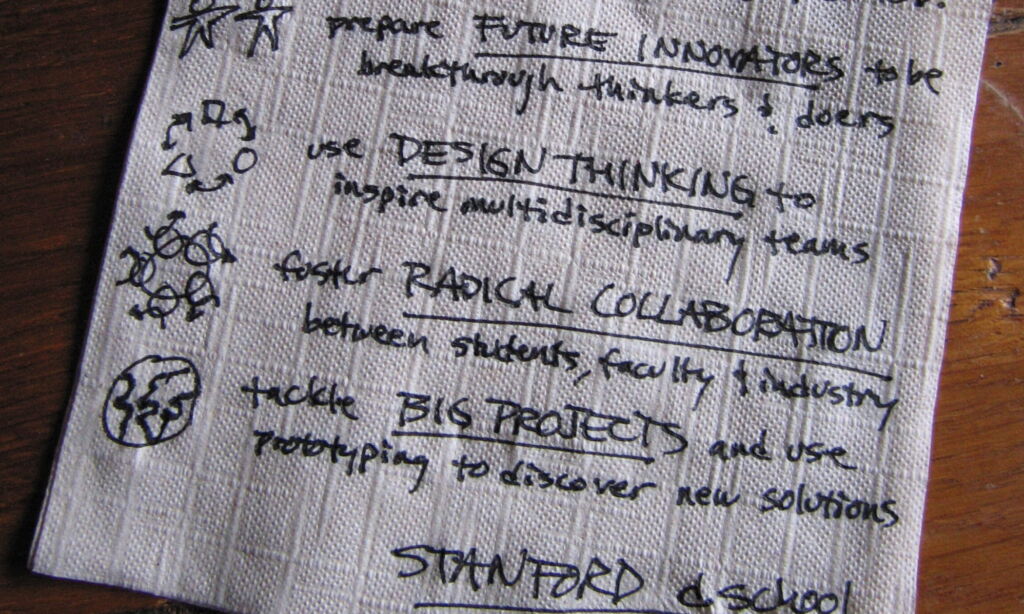

How to Start a d.school

Share Out

Story

Founding Principles

Share Out

Story

Equity Practice in Design

Share Out

Story

Exploring Emerging Tech x Design

Share Out

Story

EdTech Remix

Share Out

Story

Designing Bridges: Building Belonging and Community at the d.school

Share Out

Story

d.school Futures Series

Share Out

Story

The Deeper Learning Escape Room

Project

Story

Rep| Magazine: Emerging Tech for K12 Students and Educators

Project

Story

Reimagining School Safety

Project

Story

Designing Social Media for Youth Mental Health

Project

Story

Tackling the Opioid Crisis at the Human and Systems Levels: A Case Study

Project

Story

Integrative Design: A Practice to Tackle Complex Challenges

Share Out

Story

Shadow a Student Challenge: School Leaders Take a Crash Course in Empathy

Project

Story

Hactivation Nation: Experimenting Toward Building a Network of Deeper Learning Hackers

Share Out

Story

2018 Is the Year of the Intangibles

Educators

Story

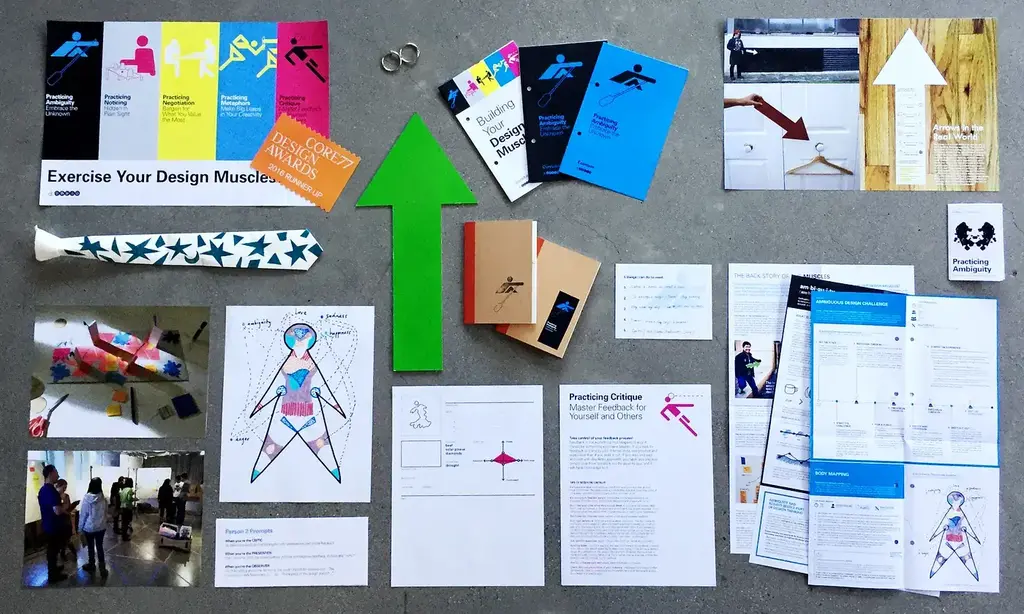

Building Your Design Muscles

Educators

Story

Bias and Creativity: Designing for Worldview

Project

Story

Using Design to Navigate the Pandemic Uncertainty: A Case Study

Social Impact

Story