On March 12, 2019 we brought together the design and futures communities at the Stanford d.school to explore the intersections between the two and deepen our collective ability to design the future we want to see.

Lisa Kay Solomon, designer in residence at the d.school, hosted Stuart Candy, Associate Professor of Design at Carnegie Mellon University; Katherine Fulton, founder of the Monitor Institute; and Olatunde Sobomehin, CEO and Lead Servant at StreetCode Academy in a panel discussion. Dozens of learners and leaders comprised of educators, students, d.school community members, industry leaders, foresight and futures practitioners, social change agents, entrepreneurs, and policymakers attended the panel and participated in the interactive mini-experiences about the future.

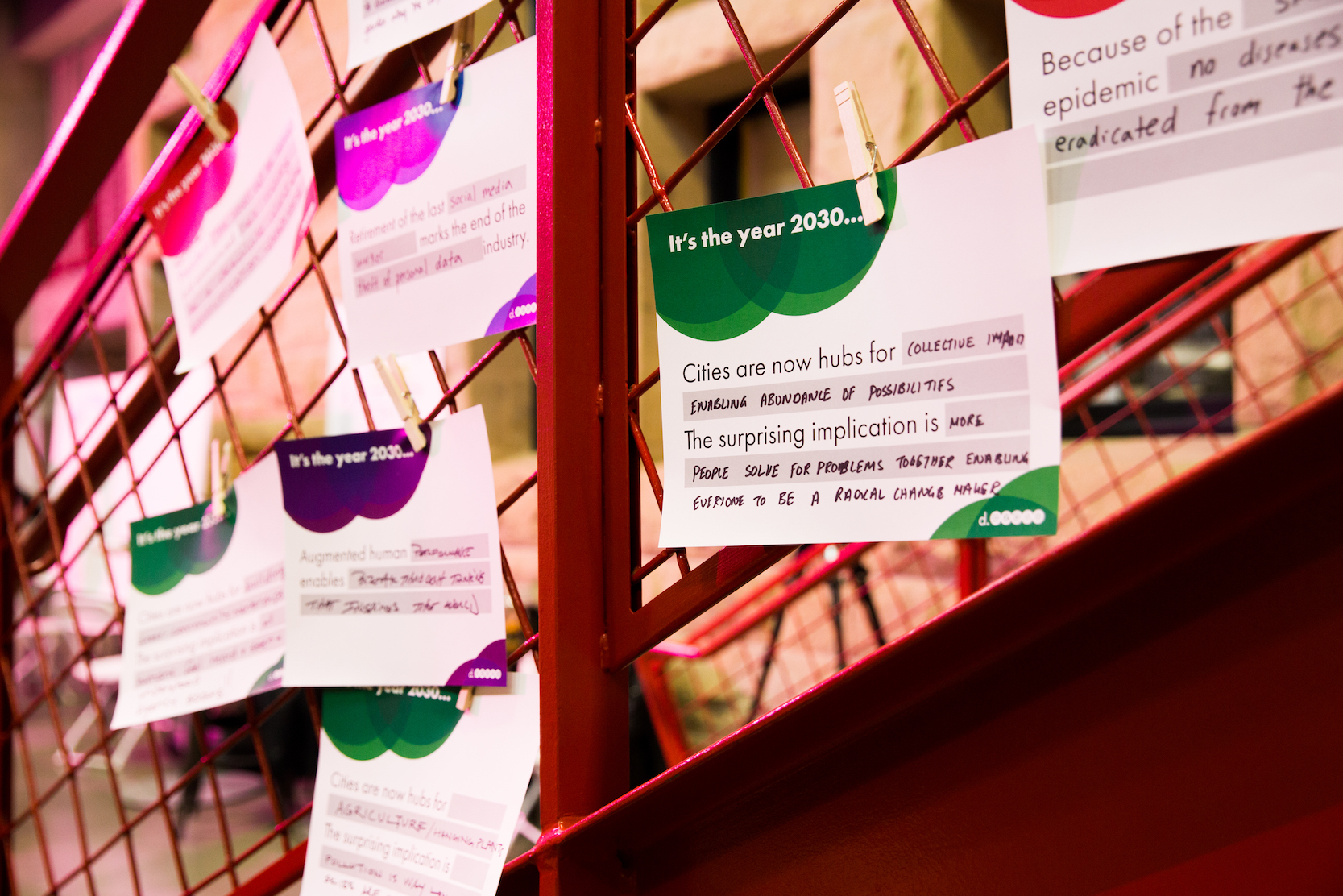

Photography by Patrick Beaudouin

Photography by Patrick Beaudouin

The Future’s Happening hoped to bring together these individuals from different areas of focus to pull in diverse perspectives in our exploration of how to design a better future. The response was overwhelming, demonstrating that there’s an appetite for this kind of multidisciplinary exploration—and that people want to take part in the conversation.

Why bring together design and futures?

Design and futures have grown as different disciplines, and have different influences, too. The time horizon especially sets the two apart. Design tends to focus on creating new solutions, opportunities, or experiences that serve people in the nearer term, whereas futures is by definition rooted in more long-term thinking.

“We wanted to push the capacity of our community to think more expansively about the range of futures that might unfold, and to articulate what’s required to bring our preferred futures to life.”

Designers also tend to be more concerned with actually making something—either tangible or intangible. Futures, on the other hand, is interested in illustrating or bringing to life new visions and reorienting the way people think about the world.

But here at the d.school, we think that the two fields ought not to be that far apart from each other. Designing the future requires imagining something that doesn’t yet exist and both designers and futurists are already uniquely good at this. Designers tend to work on creating a solution to serve the needs of a certain community or person and futurists often contemplate slightly more abstract, society-level issues—but both set themselves apart from other fields in their ability to speculate, or devise theories and ideas even without strong evidence to back them.

This is already often the case at the d.school and we hoped to further bridge that gap through the discussion Lisa hosted during the event.

Photography by Patrick Beaudouin

Why now?

The world is collectively struggling to address the increasingly urgent systemic challenges we face. Many of these issues—from climate change to income inequality—are becoming too big for us to ignore, but the solutions will not be created in a vacuum. Radical collaboration is the backbone of the d.school: we know that the best creative thinking is the result of bringing together different points of view.

“We wanted to push the capacity of our community to think more expansively about the range of futures that might unfold, and to articulate what’s required to bring our preferred futures to life,” Lisa explained. “And we hoped to connect fellow travelers, to build and deepen a diverse community of future explorers, future stewards, future leaders, and future shapers."

This is what we hoped to achieve by providing a forum in which the design and futures communities could come together. Learning about futures and from those steeped in futures will help designers discover novel ways to apply their skills and push the boundaries of how to design a better world that we all want to be part of.

“What you can try to do is create circumstances in which you can see from multiple perspectives and attempt to empathize and bridge into experiences of the past and of the present.”

The event’s panelists are already starting to think this way and are literally designing the future in their own unique ways.

Bringing futures to life

Stuart knows that it requires immense imagination to design a future that doesn’t yet exist. It also requires being able to inhabit the perspectives of other people in order to take their needs and preferences into consideration and explore how any action or decision can impact them. That’s why Stuart works on experiential design.

Photography by Patrick Beaudouin

“What you can try to do is create circumstances in which you can see from multiple perspectives and attempt to empathize and bridge into experiences of the past and of the present,” he said. Stuart and his colleagues develop virtual standpoints, to allow us to experience some version of what may lie ahead; in other words, to bring futures to life. This approach brings together the conceptual infrastructures native to futurists with the materiality and “the making things real” of design, marrying the top-down and bottom-up approaches.

Ideally, Stuart thinks that both futurists and designers should be—and often are—working toward getting people to invest their belief in the multiple directions that the future might unfold, rather than suspending their disbelief. Both communities can work together to start getting people to put their belief into a future that doesn’t yet exist.

Leading with contextual intelligence

Designing the future is an inherently abstract undertaking. But to take some of the ambiguity or abstractness out of this work, Katherine calls for relying on “contextual intelligence.” The term plays on the concept of emotional intelligence and is a skill of many successful leaders. Looking at history, many of these leaders have read the context to become the great entrepreneurs we know them to be, and to time the right innovation. Part of this is looking at what we can actually influence about a given problem.

Leaders are already ahead in this respect. From there, it is their responsibility to push people’s assumptions about what is possible; “the art is the pace and timing of how to get people to see, also to learn, at the edge of what they can learn,” she said—they simply must be careful not to push people’s assumptions too far.

Katherine encourages the leaders she works with to combine imagination and contextual intelligence to examine our collective assumptions better: what we believe, and what we think will happen, with the aim of ultimately making smarter and better decisions.

Building a better future with your own two hands

Designing the future is part of StreetCode Academy’s tagline—literally. Tunde, the organization’s founder, created it with the aim of equipping underrepresented leaders with “the skills to hack, hustle, and design the future.”

Seeing an opportunity in coding, “a skill and a literacy that is just as relevant as the ABC’s,” Tunde built StreetCode Academy with the East Palo Alto community in mind. But he knows that skills are only one of the prerequisites to build the future. That’s why mindset—empowering the students to change the world, and network—enabling the students to collaborate and take part in the conversations around the state of our world and how to change it, are equally important.

Tunde is an advocate for everyone spending time with people from a different background than their own, suggesting that “breaking down your preconceived notions and strengthening relationships will allow for a more inclusive design process.” And while he joked that he had “been wrestling with why you invited me on the panel” because he isn’t a futurist himself, StreetCode Academy is an example of designing the future in action. Tunde observed a need and developed a solution, and in so doing, he is helping others do the same for themselves.

Photography by Patrick Beaudouin

What’s next?

As Lisa highlighted, “there are no facts about the future. But how we feel about it—our posture and sense of agency around it, the processes that we use to understand and interrogate it, and our set of practices and tools to shape it—those are very much available to us today.”

Many of the participants echoed Lisa and the panelists’ sentiments: a Stanford student remarked that “the future is what you dream it will be,” while another attendee noted that “the future is already here.” Others called the future wise, abundant, and inspiring.

The overlap between design and futures may not be immediately obvious, but we hope that some of the highlights from the discussion outlined above give you just a few ideas of how they can—and already do—work together.

But this work isn’t done—this event wasn’t intended to serve as a one-time get together. Across other parts of the d.school, students and practitioners are learning about the overlap between design and emerging technology, for example, and are even able to take Lisa’s class dedicated to designing the future. The common thread among all these events and classes is the d.school’s overall effort to advance the ability of design to have a meaningful influence on the future we want to see.

The Future’s Happening was just the start of a conversation, but we hope that it will spark ideas for continued discussion and future collaboration.

Photography by Patrick Beaudouin