Professional Education

• Design is for everyone. We work with educators, social sector leaders, entrepreneurs & business leaders to grow their skills & deepen their abilities.

Workshops

About our design workshops

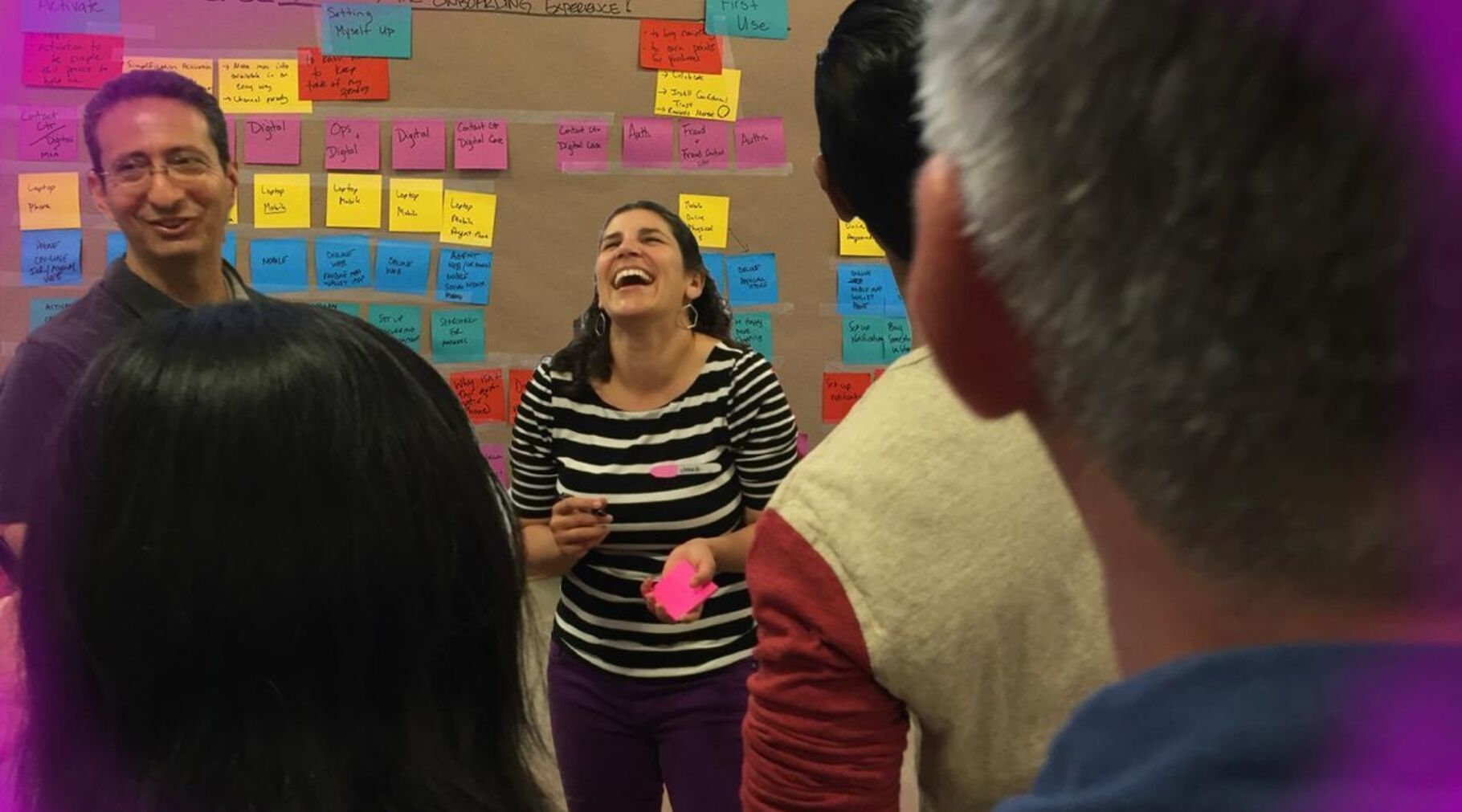

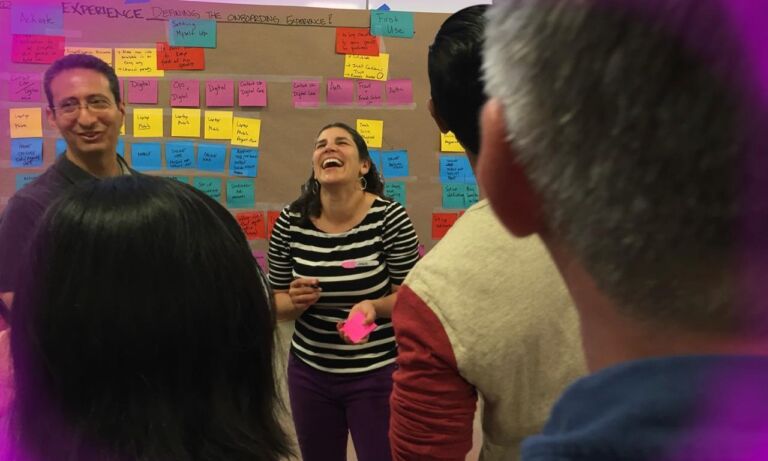

Hands-on, highly interactive, and deeply engaging—professional education at the d.school looks a little different than your typical learning experience. Expect to expand your understanding of what’s possible and to play a little.

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

All Workshops

Browse through immersive multi-day workshops or attend an event for a shorter, introductory experience.

Event

Leading with Reflection • A virtual workshop to…

Feb 25, 2026

Workshop

Online

Event

Liu Lecture: Lucy McRae

February 25, 2026

Guest Speaker

On Campus

Event

AI Micro-Series: The Future of Teamwork with AI:…

Mar 3 & 10, 2026

2-sessions

Workshop

Online

Event

Mapping What Matters • Using service design to…

Mar 4, 2026

Workshop

Online

Event

2026 Book Talk: Creative Essentials Featuring…

Feb 10, 2026

Guest Lecture

Online

Event

d.school Book Club: Creative Essentials

Jan 13-Dec 9, 2026

12 Monthly Sessions

Guest Lecture

Online

Workshop

Connecting the Dots Between Strategy and Design

Feb 4 & 11, 2026

2-sessions

Workshop

Online

Workshop

Design Thinking Bootcamp

March 24-27 or July 7-10, 2026

4-day

Workshop

On Campus

Workshop

Introductory Design Thinking Workshop

Mar 27, 2026

Workshop

On Campus

Workshop

Design for Social Impact

April 14 - May 12, 2026

5 sessions

Workshop

Online

Workshop

Teaching and Learning Studio

July 13-17 or July 27-31, 2026

5-day

Workshop

On campus

Workshop

Human-Centered AI for Social Impact

2026 Dates Coming Soon

2-day

Workshop

On Campus

Workshop

Human-Centered Design for Local Government:…

2026 Dates Coming Soon

2-sessions

Workshop

Online

updates from the d.school

Want to learn more & get involved? Subscribe to our email newsletter for (kinda) regular updates.

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER